Verifica le date inserite: la data di inizio deve precedere quella di fine

Jacopo Bedussi

Leggi i suoi articoliARTICOLI CORRELATI

Giunti al quarto giorno di sfilate, non si può ancora fare un bilancio, ma di certo si possono individuare delle tensioni, delle direzioni, intuire da che parte tira il vento. Per ragioni sia endogene (la qualità buona o ottima di diverse collezioni e show, i debutti eccellenti che accendono l’interesse) sia esogene (una crisi profonda del sistema che sembra non riuscire a trovare una strada per ripensarsi, con conseguente immobilismo creativo da parte dei marchi che prosegue ormai da anni rendendo addetti e critica molto più entusiasticamente sensibili a qualunque slancio di novità incontrino) possiamo affermare che il sentimento generale è positivo. Siamo ben lontani dai fasti di un anche recente passato, ma qualcosa si sta muovendo e l’aria, timidamente, inizia a vibrare.

È troppo presto per dirlo? Forse. Ma dopo almeno 6 stagioni sembra che la moda abbia ricominciato ad attirare attenzione, a scatenare domande, a produrre, almeno tra gli addetti ai lavori, pensiero, reazioni, interesse, fastidi, dibattito. A fare, insomma, quel che fa un’industria culturale. Speriamo bene.

Il primo dibattito l’ha inaugurato la sfilata di Prada con Rachel Tashjian che ha scritto un pezzo centratissimo e divulgativo sul «Washington Post» intitolato «In defense of truly ugly clothes» («In difesa dei vestiti veramente brutti»). Pur poi ribaltando la prospettiva e celebrando il lavoro di Miuccia Prada e Raf Simons, Tashjian parte da un presupporto-pretesto quantomeno opinabile (o, diciamolo, sbagliato) e cioè che la sfilata fosse brutta. Ora, decidere cosa sia «brutto» nella moda del 2025 è una missione persa in partenza. Per di più riferendosi a una designer, Miuccia Prada, che ha lavorato nella categoria del «brutto» sin dall’inizio della sua carriera, alla fine degli anni ’80, quando i codici della moda mainstream erano ben scritti e condivisi, e la bruttezza era facilmente riconoscibile per opposizione.

Ma oggi… senza ortodossia, come si può immaginare l’eresia?

Prada e Simons hanno proposto nel solito enorme spazio di Fondazione Prada, che quattro volte all’anno viene allestito per le sfilate, un set fatto di niente e ridotto a una pavimentazione uniforme di un arancione acceso e come soundtrack «Moments in Love» degli Art of Noise, fondamentale pezzo del 1983 che apriva la strada alla seconda ondata di musica ambient elettronica, poi esplosa all’inizio degli anni ’90, che prese anche il nome di Intelligent Dance Music. Una composizione sonora che è un collage e un montaggio di sample, puro ma elegantissimo post-moderno di lusso. Come lo sono anche i vestiti della collezione che riassociano e ricompongono momenti passati della storia del marchio, elementi che ne sono diventati il vocabolario minimo. Le divise, il militaresco, i guanti, le gonne a ruota per bene e le gonne senza forma, i sandalacci, le dust bag in raso da usare come borsette ecc. E poi ci sono le studiatissime acerbità di Simons, capi che sembrano messi su a metà dello sviluppo, come senza struttura, appena ritagliati dal cartamodello e buttati sul corpo. Il dialogo tra i due codirettori creativi si fa sempre più stratificato e insieme sfizioso, e forse tra qualche stagione il gioco per fashion-nerd di dissezionare i look e provare a indovinare da chi dei due provenga l’idea per questo o quel dettaglio non si potrà più fare. E si sarà compiuto un ciclo, chiuso un cerchio.

L’altro sorvegliato speciale è stato Dario Vitale al suo debutto da Versace. Di fronte a un rompicapo come pochi altri è difficile figurarsi nella moda: come interpretare da autore un marchio che è globalmente sinonimo di moda? Un marchio che è una bibbia estetica di segni, una saga familiare, pura letteratura o cinema, che pur avendo nel tempo perso smalto e mordente resta quasi una parte per il tutto, emblema pop che racchiude tutto ciò a cui si pensa quando si pensa alla moda. «Qui si fa Versace o si muore», dev’essersi detto Vitale. E Versace l’ha fatta, sua, eccome. Anticipata da una serie di tracce visive e riferimenti sparsi sui social senza granché spiegare, ma solo evocando, stuzzicando e sobillando, la collezione è fatta di una serie di scelte e prese di posizione molto rischiose, riuscite e radicali. Mai iconoclasta: in alcuni look tributo ci sono infatti citazioni dirette a certe sfilate di Gianni Versace da sussidiario della moda, come i look di gomma, il cowboy, le stampe pop art, le asimmetrie, i tessuti mezzo e mezzo, e così via. Una riappropriazione di uno spirito del tempo e di un modo di intendere lo status, la ricchezza e il lusso che colpisce e proietta possibilità entusiasmanti. Versace è un marchio da ricchi e privilegiati, o per chi vuole usare la moda per travestirsi da ricco e privilegiato. Anche giocando con questi codici, anche sfregiandoli.

E l’idea di sfregio e di spreco è probabilmente la forza carsica che muove il lavoro fatto da Vitale. I suoi ricchi sono quanto di più lontano possiamo immaginare dalle Kardashian o dall’ultra-polished lifestyle che impera sui social (e infatti, ancora una volta a sfregio, dall’account Instagram di Versace, niente diretta streaming). I suoi ricchi sono arroganti e sfacciati, colti, forse anche un po’ stronzi. Belli e sexy, sono tutti personaggi almeno duali. Molto consapevoli di sé non sono sterili e compiaciuti, ma anzi si sporcano, sono equivoci, si desiderano in una frenesia tutta erotica e un po’ tossica e blasé. Spreco sacro, e consumo di sé e dei corpi e del denaro per vedere l’effetto che fa. Una collezione e una sfilata inquietante e affascinante, che rimanda a qualcosa di terribile e pericoloso, e quindi sublime. Come un libro di Brett Easton Ellis.

Altra bella conferma con un pizzico di sorpresa: Marco Rambaldi, che ha proposto la sua collezione più tecnicamente (su tutto il resto, narrazione e valori, è uno a cui non c’è mai stato proprio niente da ridire) a fuoco da quando ha fondato il suo marchio. Styling curato e affilato, qualità dei capi che traspariva nei materiali quanto nel taglio e quindi poi faceva guadagnare punti in vestibilità. È un piacere, davvero. Galib Gassanof, con il suo progetto creativo Institution, dopo una solida base nelle stagioni passate costruita ragionando sui fondamentali del fare vestiti (materiali, tessuti, trame, colori), inizia ad innestare nel discorso riferimenti narrativi, considerazioni sul contemporaneo. È un passo in avanti che non risulta avventato perché rispetta il tempo della sua personale ricerca, in un territorio, che oggi è davvero difficile e inospitale economicamente parlando, che è quello della moda come linguaggio e non come industria.

Da Moschino, Adrian Appiolaza vira, nonostante qualche trovata da show, verso la dimensione della vendibilità. Ma tutto sembra ancora fuori fuoco, abbozzato, molto poco convincente in una serie di vie di mezzo che non portano da nessuna parte.

Emporio Armani è per forza di cose qualcosa che non si può nemmeno definire sfilata. La sfilata c’è, ovviamente, ed è proprio nello stile di Emporio Armani. Ma, come è giusto che sia, si tratta soprattutto di un momento sentimentale e di celebrazione, di addio. Quando le modelle, una dopo l’altra, alla fine sono uscite applaudendo compostamente, viene davvero da commuoversi. Un gesto semplice e potente, che dice tutto e rimette in ordine l’incongruo carrozzone di selfie col defunto e speculazioni sull’eredità che, con sciatteria rara, ha accompagnato sui giornali e sui social network la notizia della morte di un uomo che ha scritto mezzo secolo di eleganza.

Infine, SUNNEI, uno dei brand più interessanti costruiti a Milano negli ultimi dieci anni da Loris Messina e Simone Rizzo, che sono stati capaci di mettere in piedi un piccolo mondo, piuttosto unico, che non assomiglia quasi a nient’altro (abiti e personaggi giocosi e gelidi, sarcastici e snob). Nonché forse i soli a Milano che nelle ultime stagioni hanno rimesso in discussione il senso della sfilata, forzando i confini con invenzioni ed espedienti sempre affilati e riflessivi, ma anche spassosi (il pubblico in piedi, ad esempio, o ancora i modelli che, arrivati in fondo alla passerella, si lasciano cadere tra le mani tese degli spettatori facendo una sorta di «stage diving», oppure consegnando palette numerate agli invitati, trasformando lo show in una grande votazione dei singoli look). Stavolta, in una collaborazione con la casa d’aste Christie’s, i due si sono idealmente «messi all’incanto» con banditore superstar e aggiudicazione frenetica. Poteva sembrare un’operazione un po’ fine a sé stessa, ma giusto un paio d’ore dopo lo show tutto si è chiarito. Dopo dieci anni, i due abbandonano la direzione creativa del marchio che hanno fondato, verso nuove esperienze. Un ultimo show che è una così chiara avversione a quel sentimentalismo egotico che oggi si incontra ovunque e permea il fashion system, che viene voglia di andare lì e stringere loro la mano, augurando il meglio.

Prada Women SS26

Prada Women SS26

Milan Fashion Week: Days 3 and 4

Is the wind shifting? At Prada, a major show followed—like at a film forum—by a debate. Dario Vitale at Versace proves he knows what he’s doing—and wants to do it. At Sunnei, the creative directors are auctioned off. But even elsewhere, people are rolling up their sleeves again, and thinking has finally resumed.

By the fourth day of runway shows, it’s still too soon to make a final assessment, but it’s certainly possible to identify tensions, directions, to sense which way the wind is blowing. Due to both endogenous reasons—the good to excellent quality of several collections and shows, outstanding debuts that ignite interest—and exogenous ones—a deep systemic crisis that seems unable to reinvent itself, resulting in years of creative stagnation among brands and making industry professionals and critics much more enthusiastically receptive to any sign of novelty—we can say that the overall mood is positive. We’re still far from the glory days, even of the recent past, but something is stirring, and the air, cautiously, is starting to vibrate.Too soon to say? Perhaps. But after at least six seasons, fashion seems to be drawing attention again, provoking questions, generating—at least among insiders—thought, reactions, interest, irritation, debate. In short, doing what a cultural industry does. Let’s hope for the best.

The first debate was sparked by the Prada show, with Rachel Tashjian writing a spot-on, accessible piece for the Washington Post titled “In defense of truly ugly clothes.” While ultimately flipping the perspective and celebrating the work of Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons, Tashjian starts from a premise—if not a pretext—that is questionable (or, let’s say it, wrong): namely, that the show was ugly.

Now, trying to define what’s “ugly” in fashion in 2025 is a losing battle from the start—especially when referring to a designer like Miuccia Prada, who has been working within the category of “ugly” since the beginning of her career in the late ’80s, back when the codes of mainstream fashion were well-defined and shared, and ugliness was easily identifiable by contrast. But today… without orthodoxy, how can one imagine heresy?

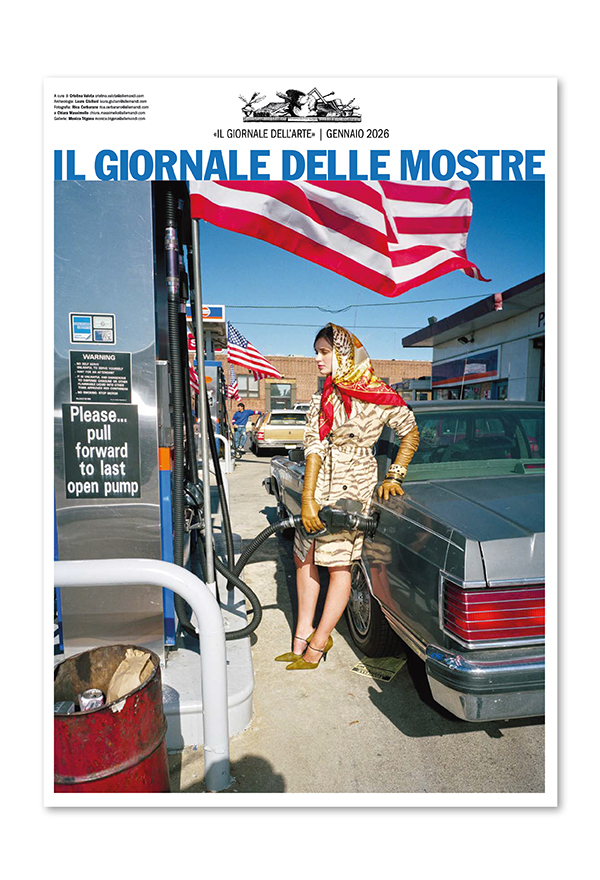

Prada and Simons presented, in the usual massive space at the Prada Foundation—transformed four times a year for shows—a set made of nothing but a uniform, vibrant orange floor, with Moments in Love by Art of Noise as the soundtrack. This seminal 1983 track paved the way for the second wave of ambient electronic music, which exploded in the early ’90s and came to be known as Intelligent Dance Music. A sonic composition that’s a collage and montage of samples, pure yet exquisitely luxurious postmodernism. Just like the clothes in the collection, which reassemble and recompose past moments from the brand’s history—elements that have become its minimal vocabulary. Uniforms, military references, gloves, demure full skirts and shapeless ones, chunky sandals, satin dust bags used as purses, and so on. Then there are Simons’s deliberately raw touches: garments that seem halfway through development, as if unstructured, just cut from the pattern and thrown on the body. The dialogue between the two co-creative directors is becoming increasingly layered and playful. And maybe in a few seasons, the fashion-nerd game of dissecting looks to guess which idea came from whom will no longer be possible. A cycle will have completed, a circle closed.

Another closely watched debut was Dario Vitale at Versace. Faced with one of the most difficult conundrums in fashion—how to interpret, as an author, a brand that is globally synonymous with fashion? A brand that is an aesthetic bible of symbols, a family saga that reads like literature or cinema, and though it’s lost some of its edge over time, still stands as a synecdoche for fashion itself. Here it’s Versace or bust, Vitale must have thought. And he did Versace. His own. Fully. Preceded by scattered visual clues and references on social media—evocative, teasing, provocative—the collection is built on a series of bold, risky, and radical choices and positions.Never iconoclastic: in fact, some looks directly pay tribute to Gianni Versace’s iconic shows—rubber outfits, cowboy aesthetics, pop art prints, asymmetries, split fabrics, and so on. But it’s ultimately a reclaiming of a zeitgeist and a way of understanding status, wealth, and luxury that stands out and opens up exciting possibilities. Versace is a brand for the rich and privileged—or for those who want to use fashion to disguise themselves as rich and privileged. Even while playing with these codes, even by defacing them. And the idea of defacement and waste is probably the underlying force in Vitale’s work. His rich are as far removed as can be from the Kardashians or the ultra-polished lifestyle dominating social media (and, again defiantly, there was no livestream on Versace’s Instagram account).

His rich are arrogant and brazen, cultured, maybe even a bit assholish. Beautiful and sexy—breasts are proud and flaunted à la Herb Ritts, crotches spectacular and framed à la Robert Mapplethorpe—they’re all characters, at least dual in nature. Highly self-aware, they’re not sterile or self-indulgent but rather get messy, are ambiguous, erotically and toxically frenzied and blasé. Sacred waste and self-consumption—of bodies, of money—just to see what happens. A disturbing and fascinating show and collection, evoking something terrible and dangerous, and thus sublime. Like a book by Bret Easton Ellis. Another pleasant confirmation—with a touch of surprise—was Marco Rambaldi, who presented his most technically refined collection since founding his brand. Styling was sharp and well-considered; the quality of the garments showed in both materials and tailoring, which in turn improved fit. A real pleasure.

Galib Gassanoff, with his label Institution, after establishing a solid base in previous seasons by focusing on the fundamentals of making clothes—materials, fabrics, textures, colors—has now begun incorporating narrative references and reflections on the contemporary. It’s a forward step that doesn’t feel rushed because it respects the rhythm of his personal research, in a terrain that is currently incredibly difficult and economically inhospitable: fashion as a language, not an industry. At Moschino, Adrian Appiolaza, despite a few showy stunts, veers toward commercial viability. But everything still feels off-kilter, underdeveloped, and largely unconvincing—a series of half-measures that lead nowhere.

Emporio Armani is, by necessity, something that can hardly be called a fashion show. Of course, the show happens—it’s precisely an Emporio Armani show. But, rightly so, it’s mostly a sentimental moment, a celebration, a farewell.And when, in the finale, the models walk out one by one applauding quietly, it’s genuinely moving. A simple, powerful gesture that says everything, and reorders the messy circus of selfies with the deceased and speculation about inheritance that, with rare carelessness, has accompanied the news of the death of a man who wrote half a century of elegance.

Finally, SUNNEI—one of the most interesting brands to emerge in Milan in the past ten years, founded by Loris Messina and Simone Rizzo. Two who managed to create a rather unique little world that resembles almost nothing else. Playful and icy clothes and characters, sarcastic and snobbish. Perhaps the only ones in Milan in recent seasons to question the very meaning of a fashion show, pushing its boundaries with consistently clever, reflective, and fun inventions—like having the audience stand while models stage-dived into their outstretched arms, or handing out numbered paddles to turn the show into a massive rating session for individual looks. This time, in collaboration with Christie’s, the two symbolically auctioned themselves off, with a superstar auctioneer and frantic bidding. It might have seemed like an operation ending in itself, but just a few hours after the show, everything became clear. After ten years, the two are stepping down from the creative direction of the brand they founded, heading toward new ventures. A final show that is such a clear rejection of the egotistical sentimentalism saturating the current fashion system, it makes you want to go shake their hands and wish them the very best.